The Medicine of Shit-Talking

I had a conversation a while back with a psychedelic facilitator who trains other providers in navigating altered states of consciousness. When I brought up to him that integrating psychedelic and spiritual experiences was inter-relational and should be grounded in community he told me “I don’t have a clue how to be in community!”. I loved his honesty, and it got me thinking even more deeply about this idea.

Being “in community” is especially tricky for those of us who grew up in dysfunctional families. If our baseline for being “in community” is dysfunctional, how do we maintain a “functioning” community?

In modern discourse, there is less talk about the intricate dynamics of being “in community” and more of a focus on cutting “toxic” people out of your life. You know those “toxic” people – the gaslighters, the manipulators and the narcissists. We are encouraged to go “no contact” or “low contact” with those people, to set our boundaries and to know our worth and to toss them right out of our community. Look, setting boundaries is good and healthy. But isn’t it all too easy to label someone else as toxic and cut them out of our life so we can avoid looking at our own toxicity? Aren’t many people creating their own bubble world where they can see themselves as a good person and ignore their manipulative parts?

This bubble world forms much of the world I know here in Portland. In social situations we are encouraged to be “good”,, to say the right thing, to be supportive and for God’s sake DO not trigger anyone!

I grew up in a vastly different culture in Arlington, Virginia in the 1980’s and 1990’s. For starters, my area was as diverse as it could get. My high school newspaper broke down our ethnicities one year, and we had 25% hispanic (mostly immigrants from Central America), 25% Asian (mostly southeast Asian immigrants), 25% white, and 25% black. The thing that bound all of us together was a culture of shit-talking.

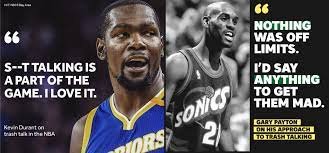

Here is how shit-talking cultures function: as soon as you enter “the community”, whether it’s at school, on the basketball court, or walking around town, people will look for your weak spot. The thing you are sensitive about, the thing you are uptight about. Your wound.

As soon as “the community” finds that, and you “react”, it’s on! An unending trigger. As soon as people see you react, (whether you’re defensive, lash out or shut down) they’ll pile on. The game is to get you to react, to get in your head.

I was a really emotional and sensitive kid so that game really got to me when I was younger. My own game centered around being called a “punk-ass white boy”. Oh my God did I hate that. It cast light on two things I was super sensitive about. First was being white. Being white was not great in Arlington. Whiteness was nerdiness, the definition of uncool. There was a black kid named Wardell in some of my classes who got it worse than me. He was smart, quiet and studious (i.e. he acted “white”) and he got called an Oreo.

Being called “white boy” also pointed to the unearned advantages I had (what today is called white privilege). At the time, I couldn’t understand white privilege. I was just as poor as everyone else. My house was dirty. I stank of dirty clothes and cigarette smoke. My parents were divorced and my mom was constantly on the verge of a mental breakdown.

The second thing I was sensitive about was being a “punk-ass”. A “punk” in that world is someone that doesn’t stand up for themselves. I certainly didn't for much of my childhood. What those kids were pointing out was a lack of pride in myself and hence a willingness to take their abuse. The “punk” in me wanted to create a shell to hide my wounds and to feel sorry for myself. People easily found that out and brought those parts to “the community” for everyone to see. After years of resisting that process and of being angry at the world, I started to embrace it. Instead of trying to run away from the abuse, I decided to meet it head on.

I wish I knew the moment it changed. I don’t think it was one moment but a series of moments held together by a thread of Spirit.

When someone fucked with me, I fucked with them back. If they called me names, I called them names. If they got in my face I got into theirs.

And a strange thing started to happen. I got a little more accepted into “the community”. I was still a “white boy”, but was a little less of a “punk-ass!” I remember hanging out one day with my black friend Greg. As we smoked some weed and listened to hip-hop, he started calling me racial epithets. I remember the moment I decided to do it back to him, calling him all sorts of names. He just laughed and it was like I passed a test. A dangerous test for sure. I started to see how shit-talking could bond us together, and we could laugh at our hang-ups and inflated sense of our precious selves.

Thank God for the bonding power of marijuana. Another time I was hanging out at a party and smoking weed with this tough black kid named Mike. The only thing I knew about him was a story that some girl had disrespected his crew and in retaliation he tagged his gang sign into her forehead with a sharpie.

As we smoked together I brought up that story. That was me saying “Hey man I’m gonna bring shit up! Let me hear where you’re at with that.” But Mike was in an introspective place. He told me he felt bad about that. That he was acting immaturely and he recognized the pain he caused her. And although Mike was able to say that, that kind of vulnerability is rare for people in a shit talking culture. In that culture, vulnerability is weakness, and weakness means you might get hurt. That’s the downside to shit-talking – you can hide your wounds under humor or toughness.

However, I am immensely grateful that I grew up in a shit-talking culture because I learned how to get triggered, get fucked with and fuck with people back without collapsing into a heap of self pity. That didn’t happen overnight though. It took me many years of being a triggered, defensive, scared boy to turn into someone that could start to play with that dynamic.

Interestingly, when I really deeply explored psychedelics, I discovered that the spirits talked to me in the same way! The spirits teased me, toyed with me, showed me my wounds and insecurities and encouraged me to laugh at myself. My Brazilian capoeira teacher Almiro had a similar way about him.

When I moved to Portland, I brought that same shit-talking mentality that I knew so well. I would call things out, fuck with people. At that time I didn’t even consider it as a part of my healing work or healing process. It was just a part of who I was, a part of my cultural identity. Some people might have called that identity “toxic”.

I found that people in Portland were in many ways much more vulnerable and open than my East Coast community. They could talk about their feelings in ways I found admirable. But I also found that they used that vulnerability as a crutch and as a weapon. They could so deeply embrace their “triggers” and their “wounds” as a way of hiding or collapsing into their shell and push away people that triggered them. Instead of fucking with you for being a “punk”, Portland holds you in esteem for embracing your wounded inner child.

At Spirit House, I recognize the need for both approaches. What a conundrum! How do we create space for people to hold their wounded inner child while also encouraging them to grow up, stand up for themselves, and not take themselves too seriously? How do we integrate the healing power of shit-talking in a culture that has no ability to see it as helpful?

Apart from some very deep friendships and intimate relationships, being “in community” in Portland has been a painful process. I don’t think most people here understand where I’m coming from with this, and I’ve definitely felt hurt and hurt others when I didn’t realize or didn't care about the cultural rules I was breaking. I’ve also done a poor job of explaining the values and beauty of shit-talking culture.

On the other hand, many people here are hungry for this approach. They whisper to me (with hints of shame!) how they’re tired of silencing themselves so that others aren’t triggered. They tell me they’ve been so trained to be a good boy or good girl that they don’t know any other way of being. And that’s where Spirit House comes in.

The clash of cultures comes alive when we have community events at Spirit House. Sometimes I’ll start to “talk shit” to someone who doesn’t understand the game and I won’t find out until weeks or months later that I‘ve hurt their feelings. Sometimes I notice it in the moment when they freeze up.

Either way, my game now is to develop a “layered approach” to shit-talking— to gradually introduce the medicine in a way that gives people time to digest and integrate it. One could even call this approach trauma-informed!